Persecuted/Persecutors, People of the 20th Century

8 March to 15 November 2018

The Memorial’s resources on the “August Sander. Persecuted/Persecutors, People of the 20th Century” exhibition can help you research or deepen or your knowledge of the topic.

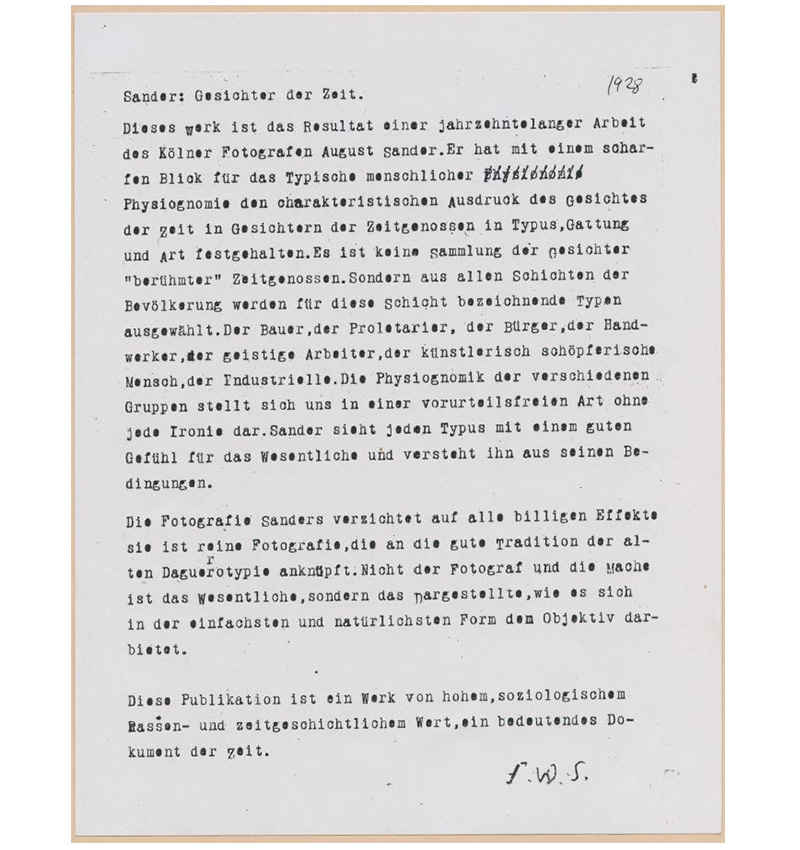

Letter from Franz Wilhelm Seiwert to August Sander, 1928

A year after the Kunstverein exhibition in Cologne, August Sander planned a trip to Berlin with an eye to photographing figures on the city’s art scene for his “People of the 20th Century” project. Franz Wilhelm Seiwert wrote him this letter of introduction (translation by Bender & Partner).

Sander : Faces of our Time.

This book stems from a decade of work by Cologne photographer August Sander. His sharp eye allows him to detect the uniqueness of human physiognomy, thereby fixing, through the type, kind and way of being of his contemporaries, the characteristic expression of the face of his time. This is not a collection of “famous” people’s faces. Sander has chosen to focus on individuals from all walks of life: the farmer, worker, citizen, craftsman, intellectual, artist, industrialist, etc. He offers us the physiognomy of various groups without preconceived ideas or a shred of irony. He considers each typical figure with an innate sense for the essential and respect for his living conditions.

Sander eschews all forms of vulgar effects. His work is photography in its purest state, recalling the daguerreotype tradition. Neither he nor his processes are essential, but rather the subject photographed, as offered to the lens in the simplest, most natural form.

From the viewpoints of both racial sociology and history, this publication is a work of tremendous value — a significant document of our time.

F.W.S.

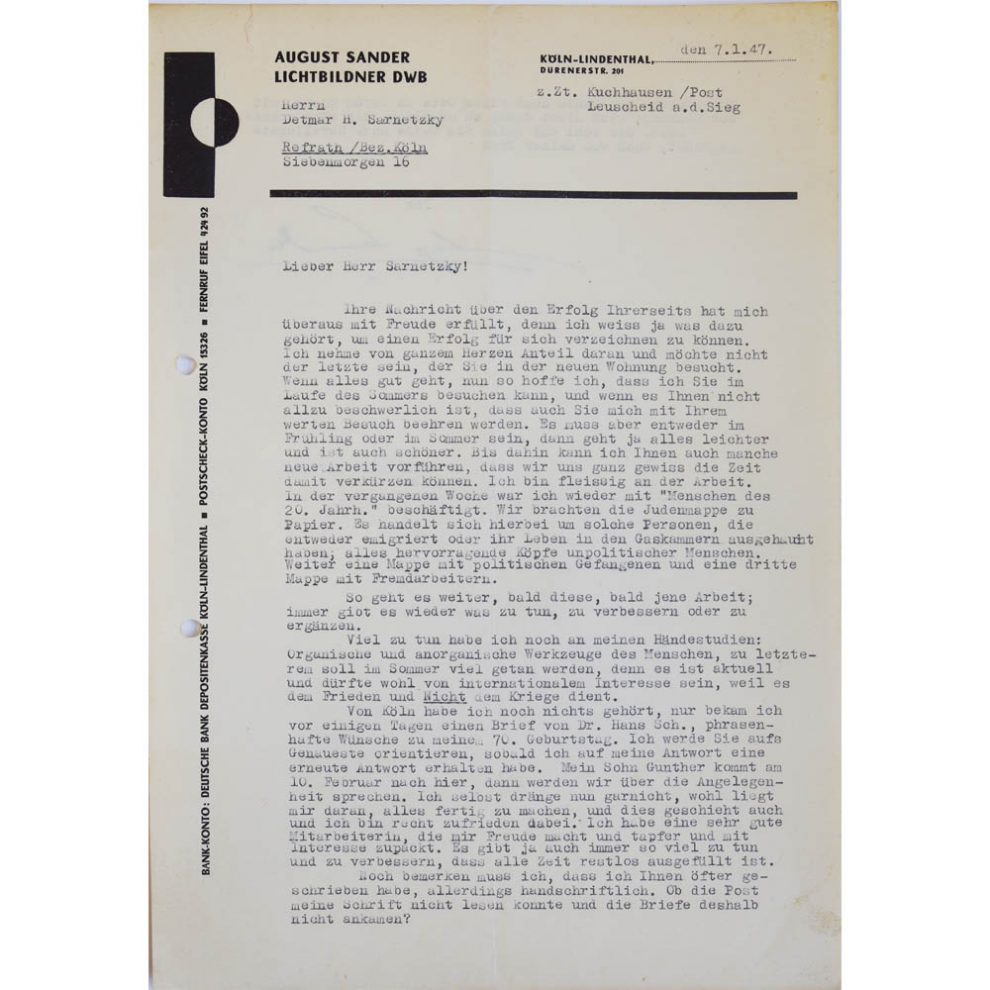

Lettre d’August Sander à Dettmar Heinrich Sarnetzki, 7 janvier 1947

August Sander wrote to the writer and editor-in-chief Dettmar Heinrich Sarnetzki about “People of the 20th Century”, mentioning the project’s organization into portfolios of Jews, political prisoners and foreign workers.

Dear Mr. Sarnetzky [sic]!

The news of your success has filled me with joy, for I am well aware of the hard work required to reap the fruits of one’s labor. I am very happy for you and look forward to visiting you in your new apartment. […]

Last week, I worked on the “People of the 20th Century” project. We have developed the prints for the Jewish portfolio. These are people who emigrated or perished in the gas chambers. Nothing but beautiful apolitical faces. We have also developed the prints for the portfolios of political prisoners and foreign workers.

I am plodding ahead, working on one project or another. There is always something to do, improve or complete. My studies of hands still require much work: man’s organic and inorganic tools, which I concentrate on mainly in the summertime because the subject is topical and likely to arouse international interest, for it serves peace and not war.

[…] I have an excellent assistant, with whom I am very satisfied and who courageously helps me and shows an interest in my work. There is always so much to do and correct that our days are quite full.

[…] // Best wishes for your move. Try not to catch cold. That would be a shame.

Take care. My wife joins me in sending you our best wishes.

Your August Sander

Les Juifs de Cologne

Scene of humiliation. Benjamin Katz and his son Arnold are paraded through the streets of Cologne on April 1, 1933 during the boycott of Jewish shops. © Fonds d’archives du Mémorial de la Shoah

– August Sander, “Persecuted” [Benjamin Katz], ca. 1938, contact print, 1990-2011. © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur-August Sander Archiv, Cologne; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; ADAGP, Paris, 2018. Courtesy of Gallery Julian Sander, Cologne and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

Interview with Gerhard and Julian Sander, August Sander’s heirs

Why did you agree to the Shoah Memorial’s proposal to organize this exhibition?

Gerd Sander: It’s very simple. I think the Shoah Memorial is the most appropriate venue for such an exhibition. And it’s the first memorial institution that made the request. Nobody had ever imagined a show like this. I was very lucky when Alain Sayag gave Sophie Nagiscarde, the co-curator, my contact details. We met in Paris, where I told her everything I know and gave her books. When two people who meet face-to-face find themselves on the same wavelength, it means you’ve found a real partner. I’m really glad that the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah made everything possible. I put a lot of myself into the project because it’s a way of continuing everything I started when I took over the reins in 1988.

Julian Sander: The world sees history as a rather limited set of various motives and causes. Reality is not always so simple. This show allowed me to focus on a very important subject and a time when a whole country was manipulated to the point of turning away from its own moral foundations. The precision and straightforwardness of Sander’s work make it a priceless tool in analyzing that. It delays our judgment, challenging us to imagine how we would have reacted to the poison spread by Nazi propaganda, and by other kinds of propaganda today.

In your opinion, how does August Sander’s work fit into the transmission of the memory of the Second World War and the Holocaust?

GS: August Sander always felt that his photos were also documentation tools. “I want to document my times,” he would say. That’s why he was so set on adding the different groups present in the “People of the 20th Century” show. Because they’re part of history. Because that’s the way it was. He lived through the 12 terrible years from National Socialism to end of the Second World War, like so many in Germany. He was harassed by the Gestapo, like so many were. We must understand that the notion of secrecy does not exist in Sander’s work. The secret is his personality. His eye and his spirit were very special. He processed everything he saw in the same way, with the same objectivity, with or without a camera. That was true for everything he undertook.

JS: August Sander made a portrait of the people of his times. His photos subtly, delicately capture the underlying characteristics of individuals from all walks of life. His commitment allowed him to capture a form of visual communication, timeless moments. Looking at his photos, you can peer into the gazes and the souls of the people of that time. That form of clear-sightedness transcends all forms of distraction. Sander’s universal respect for his subjects shows us how to perceive these people. In the context of the Second World War and the Holocaust, his gaze stands in extremely sharp contrast to reality as we know it.

What is August Sander’s photographic legacy today?

GS: I think he left us three very simple recommendations: “look, observe, think”. We should think about what we do. Think about what we say. Think about what we photograph. And why we do it. What is the aim of photography, thought, writing? What do we wish to accomplish? Just common sense, nothing more, nothing less.

JS: August Sander’s legacy is so deeply ingrained in the DNA of contemporary photography that the question is not an easy one. His work combines all the skills of his trade as well as great intellectual depth. Generations of artists have been guided and influenced by his vision of photography, some by the conceptual rigor with which he carried out the great project of his life, others by the clarity and humanism of his gaze. He set the standard for the photographic portrait, a model to live up to.

Three questions for Johann Chapoutot, professor of contemporary history at the Sorbonne (Sorbonne University) specializing in Nazism

How can August Sander’s decision to include his portraits of Cologne’s Jews in “People of the 20th Century” be interpreted?

Integrating Jews as well as other categories of people that the Nazis discriminated against and persecuted (“Fremdarbeiter”, “the sick”, “asocials”) into his collection of portraits was a full-blown act of defiance and resistance. Born into a working-class family, August Sander was a Social Democrat who never crossed the threshold of direct action against the Nazis, unlike his son Erich, a Communist who was arrested in 1934 and died in detention in 1944. The son went underground, the father carried on with his work. But making portraits of Jews was a subversive act. Under the Third Reich, portraits of Jews were either mug shots or anthropometric-scientific photographs. By making them without being a policeman or a biologist, he restored their humanity, personality and dignity. In a way, you might say he was doing what he had done for decades, when he photographed the common people and the upper classes in the same way. Only now, the subversion is no longer sociological, but political.

What do August Sander’s photos teach us about Nazism?

Not much on the surface, quite a lot if you can read between the lines. His portraits show ordinary looking, run-of-the-mill, rather likeable Nazis. Even the SS, with his pudgy cheeks, round spectacles and good-natured smile, looks like an ideal neighbor and a good dad. What can be inferred from this? At first glance, that Nazism was popular across the social spectrum and that not all Nazis were frightening and hideous. Sander also photographed their often-indirect victims: we find pathetic losers, cute faces—a great human diversity. The first conclusion is that, as the Nazis were busy obsessively categorizing people (the good and the beautiful, the Germans and the ugly, the losers and the misfits), Sander’s documentary photography was a slap in the face.

August Sander made portraits of people from all walks of German life, which ran counter to the ideals of National Socialism and Nazi propaganda. Can this be seen more as a political act than as documentary work?

It can, and that’s the second conclusion. The Nazis constructed biological, racial typologies and thought in terms of masses, “movement”, the “people’s body”, the “people’s community”. Sander photographed individuals. One of the Nazis’ many slogans was, “You are nothing, your people is everything”, which targeted German and Jew alike. There are no individuals, the harmful legacy of the French revolution, only masses defined by scientific categories—race. What Sander says just by clicking on his camera’s shutter release is simple: you, the Jew, are first and foremost an individual, with dignity and worth. You, the Nazi, are not just a nameless member of the “people’s community” following the “movement”, and you cannot hide behind your uniform. You are an individual, with a face, an address, ID papers: you are free, you have made a choice, therefore you are responsible. That two-pronged approach is tremendously subversive: the photographer restores the individual and re-institutes the society of political modernity, of free individuals who embrace causes and make choices (the murderers), and of the persecuted, who are not just a degraded biomass, but human beings endowed with dignity and value. Sander was political quite simply by pursuing his documentary work. That is his strength: he remained modest, he was never grandiloquent, he never made any ringing declarations. He simply got on with his work as a sociologist of Germany who made a portrait of German society, against the Nazi community.